Format

The sign-magnitude binary format is the simplest conceptual format. To represent a number in sign-magnitude, we simply use the leftmost bit to represent the sign, where 0 means positive, and the remaining bits to represent the magnitude (absolute value).

A 8-bit sign-magnitude number would appear as follows:

Table 4.3. 8-bit sign-magnitude format

| Sign | Magnitude |

| 7 | 6-0 |

Negation

To negate sign-magnitude numbers, simply toggle the sign bit. Note that this leads to having two representations for the number zero.

Conversions

What are the decimal values of the following 8-bit sign-magnitude numbers?

- 10000011 = -3

- 00000101 = +5

- 11111111 = ?

- 01111111 = ?

Represent the following in 8-bit sign-magnitude:

- -15 = 10001111

- +7 = 00000111

- -1 = ?

Addition and Subtraction

Addition and subtraction require attention to the sign bit. If the signs are the same, we simply add the magnitudes as unsigned numbers and watch for overflow. If the signs differ, we subtract the smaller magnitude from the larger, and keep the sign of the larger.

Range

Since the magnitude is an unsigned binary number, range is computed as it is for unsigned binary, but with one less bit. Hence, for 8-bit sign-magnitude, the range is +/- 27-1.

Comparison

Comparison works as with unsigned binary if the signs are the same. If the signs differ, the positive value is larger.

Signed Binary Numbers

In mathematics, positive numbers (including zero) are represented as unsigned numbers. That is we do not put the +ve sign in front of them to show that they are positive numbers. However, when dealing with negative numbers we do use a -ve sign in front of the number to show that the number is negative in value and different from a positive unsigned value, and the same is true with signed binary numbers.

However, in digital circuits there is no provision made to put a plus or even a minus sign to a number, since digital systems operate with binary numbers that are represented in terms of “0’s” and “1’s”. When used together in microelectronics, these “1’s” and “0’s”, called a bit (being a contraction of BInary digiT), fall into several range sizes of numbers which are referred to by common names, such as a byte or a word. We have also seen previously that an 8-bit binary number (a byte) can have a value ranging from 0 (000000002) to 255 (111111112), that is 28 = 256 different combinations of bits forming a single 8-bit byte. So for example an unsigned binary number such as: 010011012 = 64 + 8 + 4 + 1 = 7710 in decimal. But Digital Systems and computers must also be able to use and to manipulate negative numbers as well as positive numbers. Mathematical numbers are generally made up of a sign and a value (magnitude) in which the sign indicates whether the number is positive, ( + ) or negative, ( – ) with the value indicating the size of the number, for example 23, +156 or -274. Presenting numbers is this fashion is called “sign-magnitude” representation since the left most digit can be used to indicate the sign and the remaining digits the magnitude or value of the number. Sign-magnitude notation is the simplest and one of the most common methods of representing positive and negative numbers either side of zero, (0). Thus negative numbers are obtained simply by changing the sign of the corresponding positive number as each positive or unsigned number will have a signed opposite, for example, +2 and -2, +10 and -10, etc.

But how do we represent signed binary numbers if all we have is a bunch of one’s and zero’s. We know that binary digits, or bits only have two values, either a “1” or a “0” and conveniently for us, a sign also has only two values, being a “+” or a “–“. Then we can use a single bit to identify the sign of a signed binary number as being positive or negative in value. So to represent a positive binary number (+n) and a negative (-n) binary number, we can use them with the addition of a sign. For signed binary numbers the most significant bit (MSB) is used as the sign bit. If the sign bit is “0”, this means the number is positive in value. If the sign bit is “1”, then the number is negative in value. The remaining bits in the number are used to represent the magnitude of the binary number in the usual unsigned binary number format way.

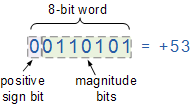

Then we can see that the Sign-and-Magnitude (SM) notation stores positive and negative values by dividing the “n” total bits into two parts: 1 bit for the sign and n–1 bits for the value which is a pure binary number. For example, the decimal number 53 can be expressed as an 8-bit signed binary number as follows.

Positive Signed Binary Numbers

Negative Signed Binary Numbers

The disadvantage here is that whereas before we had a full range n-bit unsigned binary number, we now have an n-1 bit signed binary number giving a reduced range of digits from:

-2(n-1) to +2(n-1)

So for example: if we have 4 bits to represent a signed binary number, (1-bit for the Sign bit and 3-bits for the Magnitude bits), then the actual range of numbers we can represent in sign-magnitude notation would be:

-2(4-1) – 1 to +2(4-1) – 1

-2(3) – 1 to +2(3) – 1

-7 to +7

Whereas before, the range of an unsigned 4-bit binary number would have been from 0 to 15, or 0 to F in hexadecimal, we now have a reduced range of -7 to +7. Thus an unsigned binary number does not have a single sign-bit, and therefore can have a larger binary range as the most significant bit (MSB) is just an extra bit or digit rather than a used sign bit. Another disadvantage here of the sign-magnitude form is that we can have a positive result for zero, +0 or 00002, and a negative result for zero, -0 or 10002. Both are valid but which one is correct.

Signed Binary Numbers Example No1

Convert the following decimal values into signed binary numbers using the sign-magnitude format:

Note that for a 4-bit, 6-bit, 8-bit, 16-bit or 32-bit signed binary number all the bits MUST have a value, therefore “0’s” are used to fill the spaces between the leftmost sign bit and the first or highest value “1”.The sign-magnitude representation of a binary number is a simple method to use and understand for representing signed binary numbers, as we use this system all the time with normal decimal (base 10) numbers in mathematics. Adding a “1” to the front of it if the binary number is negative and a “0” if it is positive.

However, using this sign-magnitude method can result in the possibility of two different bit patterns having the same binary value. For example, +0 and -0 would be 0000 and 1000 respectively as a signed 4-bit binary number. So we can see that using this method there can be two representations for zero, a positive zero ( 00002 ) and also a negative zero ( 10002 ) which can cause big complications for computers and digital systems.

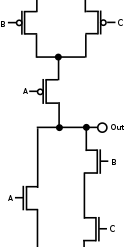

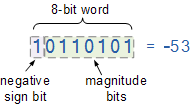

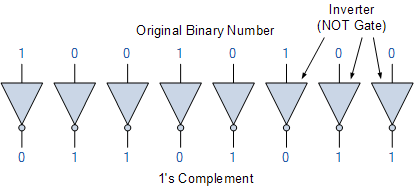

One’s Complement of a Signed Binary Number

One’s Complement or 1’s Complement as it is also termed, is another method which we can use to represent negative binary numbers in a signed binary number system. In one’s complement, positive numbers (also known as non-complements) remain unchanged as before with the sign-magnitude numbers. Negative numbers however, are represented by taking the one’s complement (inversion, negation) of the unsigned positive number. Since positive numbers always start with a “0”, the complement will always start with a “1” to indicate a negative number. The one’s complement of a negative binary number is the complement of its positive counterpart, so to take the one’s complement of a binary number, all we need to do is change each bit in turn. Thus the one’s complement of “1” is “0” and vice versa, then the one’s complement of 100101002 is simply 011010112 as all the 1’s are changed to 0’s and the 0’s to 1’s. The easiest way to find the one’s complement of a signed binary number when building digital arithmetic or logic decoder circuits is to use Inverters. The inverter is naturally a complement generator and can be used in parallel to find the 1’s complement of any binary number as shown.

1’s Complement Using Inverters

Then we can see that it is very easy to find the one’s complement of a binary number N as all we need do is simply change the 1’s to 0’s and the 0’s to 1’s to give us a -N equivalent. Also just like the previous sign-magnitude representation, one’s complement can also have n-bit notation to represent numbers in the range from: -2(n-1) and +2(n-1) – 1. For example, a 4-bit representation in the one’s complement format can be used to represent decimal numbers in the range from -7 to +7 with two representations of zero: 0000 (+0) and 1111 (-0) the same as before.

Addition and Subtraction Using One’s Complement

One of the main advantages of One’s Complement is in the addition and subtraction of two binary numbers. In mathematics, subtraction can be implemented in a variety of different ways as A – B, is the same as saying A + (-B) or -B + A etc. Therefore, the complication of subtracting two binary numbers can be performed by simply using addition.

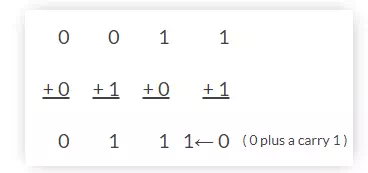

We saw in the Binary Adder tutorial that binary addition follows the same rules as for the normal addition except that in binary there are only two bits (digits) and the largest digit is a “1”, (just as “9” is the largest decimal digit) thus the possible combinations for binary addition are as follows:

When the two numbers to be added are both positive, the sum A + B, they can be added together by means of the direct sum (including the number and bit sign), because when single bits are added together, “0 + 0”, “0 + 1”, or “1 + 0” results in a sum of “0” or “1”. This is because when the two bits we want to be added together are odd (“0” + “1” or “1 + 0”), the result is “1”. Likewise when the two bits to be added together are even (“0 + 0” or “1 + 1”) the result is “0” until you get to “1 + 1” then the sum is equal to “0” plus a carry “1”. Let’s look at a simple example.

Subtraction of Two Binary Numbers

An 8-bit digital system is required to subtract the following two numbers 115 and 27 from each other using one’s complement. So in decimal this would be: 115 – 27 = 88.

First we need to convert the two decimal numbers into binary and make sure that each number has the same number of bits by adding leading zero’s to produce an 8-bit number (byte). Therefore:

11510 in binary is: 011100112

2710 in binary is: 000110112

Now we need to find the complement of the second binary number, (00011011) while leaving the first number (01110011) unchanged. So by changing all the 1’s to 0’s and 0’s to 1’s, the one’s complement of 00011011 is therefore equal to 11100100.

Adding the first number and the complement of the second number gives:

| 01110011 |

| + 11100100 |

| Overflow → 1 01010111 |

Since the digital system is to work with 8-bits, only the first eight digits are used to provide the answer to the sum, and we simply ignore the last bit (bit 9). This bit is call an “overflow” bit. Overflow occurs when the sum of the most significant (left-most) column produces a carry forward. This overflow or carry bit can be ignored completely or passed to the next digital section for use in its calculations. Overflow indicates that the answer is positive. If there is no overflow then the answer is negative.

The 8-bit result from above is: 01010111 (the overflow “1” cancels out) and to convert it back from a one’s complement answer to the real answer we now have to add “1” to the one’s complement result, therefore:

| 01010111 |

| + 1 |

| 01011000 |

So the result of subtracting 27 ( 000110112 ) from 115 ( 011100112 ) using 1’s complement in binary gives the answer of: 010110002 or (64 + 16 + 8) = 8810 in decimal.

Then we can see that signed or unsigned binary numbers can be subtracted from each other using One’s Complement and the process of addition. Binary adders such as the TTL 74LS83 or 74LS283 can be used to add or subtract two 4-bit signed binary numbers or cascaded together to produce 8-bit adders complete with carry-out.

Two’s Complement of a Signed Binary Number

Two’s Complement or 2’s Complement as it is also termed, is another method like the previous sign-magnitude and one’s complement form, which we can use to represent negative binary numbers in a signed binary number system. In two’s complement, the positive numbers are exactly the same as before for unsigned binary numbers. A negative number, however, is represented by a binary number, which when added to its corresponding positive equivalent results in zero. In two’s complement form, a negative number is the 2’s complement of its positive number with the subtraction of two numbers being A – B = A + ( 2’s complement of B )using much the same process as before as basically, two’s complement is one’s complement + 1. The main advantage of two’s complement over the previous one’s complement is that there is no double-zero problem plus it is a lot easier to generate the two’s complement of a signed binary number. Therefore, arithmetic operations are relatively easier to perform when the numbers are represented in the two’s complement format.

Let’s look at the subtraction of our two 8-bit numbers 115 and 27 from above using two’s complement, and we remember from above that the binary equivalents are:

11510 in binary is: 011100112

2710 in binary is: 000110112

Our numbers are 8-bits long, then there are 28 digits available to represent our values and in binary this equals: 1000000002 or 25610. Then the two’s complement of 2710 will be:

(28)2 – 00011011 = 100000000 – 00011011 = 111001012

The complementation of the second negative number means that the subtraction becomes a much easier addition of the two numbers so therefore the sum is: 115 + ( 2’s complement of 27 ) which is:

01110011 + 11100101 = 1 010110002

As previously, the 9th overflow bit is disregarded as we are only interested in the first 8-bits, so the result is: 010110002 or (64 + 16 + 8) = 8810 in decimal the same as before.